Societal attitudes toward homosexuality

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ rights |

|---|

|

| Lesbian ∙ Gay ∙ Bisexual ∙ Transgender ∙ Queer |

|

|

Societal attitudes toward homosexuality vary greatly across different cultures and historical periods, as do attitudes toward sexual desire, activity and relationships in general. All cultures have their own values regarding appropriate and inappropriate sexuality; some sanction same-sex love and sexuality, while others may disapprove of such activities in part.[1] As with heterosexual behaviour, different sets of prescriptions and proscriptions may be given to individuals according to their gender, age, social status or social class.

Many of the world's cultures have, in the past, considered procreative sex within a recognized relationship to be a sexual norm—sometimes exclusively so, and sometimes alongside norms of same-sex love, whether passionate, intimate or sexual. Some sects within some religions, especially those influenced by the Abrahamic tradition, have censured homosexual acts and relationships at various times, in some cases implementing severe punishments.[2] Homophobic attitudes in society can manifest themselves in the form of anti-LGBT discrimination, opposition to LGBT rights, anti-LGBT hate speech, and violence against LGBT people.

Since the 1970s, much of the world has become more accepting of homosexual acts and relationships.[3] Cross-national differences in acceptance can be explained by three factors: the strength of democratic institutions, the level of economic development, and the religious context of the places where people live.[4] The Pew Research Center's 2013 Global Attitudes Survey "finds broad acceptance of homosexuality in North America, the European Union, and much of Latin America, but equally widespread rejection in predominantly Muslim nations and in Africa, as well as in parts of Asia and in Russia". The survey also finds "acceptance of homosexuality is particularly widespread in countries where religion is less central in people's lives. These are also among the richest countries in the world. In contrast, in poorer countries with high levels of religiosity, few believe homosexuality should be accepted by society. Age is also a factor in several countries, with younger respondents offering far more tolerant views than older ones. And while gender differences are not prevalent, in those countries where they are, women are consistently more accepting of homosexuality than men."[5]

Difficulties in interpreting homosexuality

[edit]Contemporary scholars caution against applying modern Western assumptions about sex and gender to other times and places; what looks like same-sex sexuality to a Western observer may not be "same-sex" or "sexual" at all to the people engaging in such behaviour. For example, in the Bugis cultures of Sulawesi, a female who dresses and works in a masculine fashion and marries a woman is seen as belonging to a third gender;[6] to the Bugis, their relationship is not homosexual (see sexual orientation and gender identity). In the case of 'Sambia' (a pseudonym) boys in New Guinea who ingest the semen of older males to aid in their maturation,[7] it is disputed whether this is best understood as a sexual act at all.[8] Some scholars have argued that notions of a homosexual and heterosexual identity, as they are currently known in the Western world, only began to emerge in Europe in the mid to late 19th century,[9][10] though others challenge this.[11][12] Behaviors that today would be widely regarded as homosexual, at least in the West, enjoyed a degree of acceptance in around three-quarters of the cultures surveyed in Patterns of Sexual Behavior (1951).[13]

Measuring attitudes toward homosexuality

[edit]| Pew Global Attitudes Project 2019: #1 – Homosexuality should be accepted by society, #2 – Homosexuality should not be accepted by society"[1] | ||

| Country | #1 | #2 |

|---|---|---|

| North America | ||

| Canada | 85% | 10% |

| United States | 72% | 21% |

| Europe | ||

| Sweden | 94% | 5% |

| Netherlands | 92% | 8% |

| Spain | 89% | 10% |

| Germany | 86% | 11% |

| France | 86% | 11% |

| United Kingdom | 86% | 11% |

| Italy | 75% | 20% |

| Czech Republic | 59% | 26% |

| Greece | 53% | 40% |

| Hungary | 49% | 39% |

| Poland | 47% | 42% |

| Slovakia | 44% | 46% |

| Bulgaria | 32% | 48% |

| Lithuania | 28% | 45% |

| Ukraine | 14% | 69% |

| Russia | 14% | 74% |

| Middle East | ||

| Israel | 47% | 45% |

| Turkey | 25% | 57% |

| Lebanon | 13% | 85% |

| Asia/Pacific | ||

| Australia | 81% | 18% |

| Philippines | 73% | 24% |

| Japan | 68% | 22% |

| South Korea | 44% | 53% |

| India | 37% | 37% |

| Indonesia | 9% | 80% |

| Latin America | ||

| Argentina | 76% | 19% |

| Mexico | 69% | 24% |

| Brazil | 67% | 23% |

| Africa | ||

| South Africa | 54% | 38% |

| Kenya | 14% | 83% |

| Tunisia | 9% | 72% |

| Nigeria | 7% | 91% |

From the 1970s, academics have researched attitudes held by individuals toward lesbians, gay men and bisexuals, and the social and cultural factors that underlie such attitudes. Numerous studies have investigated the prevalence of acceptance and disapproval of homosexuality, and have consistently found correlates with various demographic, psychological, and social variables. For example, studies (mainly conducted in the United States) have found that heterosexuals with positive attitudes towards homosexuality are more likely to be female, white, young, non-religious, well-educated, politically liberal or moderate, and have close personal contact with homosexuals who are out.[14] They are also more likely to have positive attitudes towards other minority groups[15] and are less likely to support traditional gender roles.[16] Several studies have also suggested that heterosexual females' attitudes towards gay men are similar to those towards lesbians, and some (but not all) have found that heterosexual males have a more positive attitude toward lesbians.[16][17][18] Herek (1984) found that heterosexual females tended to exhibit equally positive or negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. The heterosexual males, however, tended to respond more negatively, or unfavorably, to gay men than lesbians.[19]

Social psychologists such as Gregory Herek have examined underlying motivations for homophobia (hostility toward lesbians and gays), and cultural theorists have noted how portrayals of homosexuality often center around stigmatized phenomena such as AIDS, pedophilia, and gender variance. The extent to which such portrayals are stereotypes is disputed.

Contemporary researchers have measured attitudes held by heterosexuals toward gay men and lesbians in a number of different ways.[20]

Certain populations are also found to accept homosexuality more than others. In the United States, African-Americans are generally less tolerant of homosexuality than European or Hispanic Americans.[21] However, polls after President Barack Obama's public support of same-sex marriage showed a shift in attitudes to 59% support among African Americans, 60% among Latinos and 50 percent among White Americans.[22] Israelis were found to be the most accepting of homosexuality among Middle Eastern nations and Israeli laws and culture reflect that. According to a 2007 poll, a strong majority of Israeli Jews say they would accept a gay child and go on with life as usual.[23] A 2013 Haaretz poll found that most of the Arab and Haredi sector saw homosexuality negatively, while the majority of secular and traditional Jews say they support equal rights for gay couples.[24]

Much less research has been conducted into societal attitudes toward bisexuality.[25] What studies do exist suggest that the attitude of heterosexuals toward bisexuals mirrors their attitude toward homosexuals,[26] and that bisexuals experience a similar degree of hostility, discrimination, and violence relating to their sexual orientation as do homosexuals.[27]

Research (mainly conducted in the United States) show that people with more permissive attitudes on sexual orientation issues tend to be younger, well-educated, and politically liberal. Tolerance toward homosexuality and bisexuality have been increasing with time. A 2011 Public Policy Polling survey found that 48 percent of voters in the state of Delaware supported the legalization of same-sex marriage, while 47 were opposed and 5 percent were not sure.[28] A 2011 poll by Lake Research Partners showed that 62% in Delaware favored allowing same-sex couples to form civil unions, while 31% were opposed, and 7% were not sure.[29]

Same-sex marriage

[edit]- Opinion polls for same-sex marriage by country

| Country | Pollster | Year | For[a] | Against[a] | Neither[b] | Margin of error |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% |

73% (74%) |

1% | [30] | ||

| Institut d'Estudis Andorrans | 2013 | 70% (79%) |

19% (21%) |

11% | [31] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | – | – | [32] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (81%) |

16% [9% support some rights] (19%) |

15% not sure | ±5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 67% (72%) |

26% (28%) |

7% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 3% (3%) |

96% (97%) |

1% | ±3% | [35] [36] | |

| 2021 | 46% |

[37] | |||||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 64% (73%) |

25% [13% support some rights] (28%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 75% (77%) |

23% | 2% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 65% (68%) |

30% (32%) |

5% | [38] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2015 | 11% | – | – | [39] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 16% (16%) |

81% (84%) |

3% | ±4% | [35] [36] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (78%) |

19% [9% support some rights] (22%) |

12% not sure | ±5% | [33] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% | 19% | 2% not sure | [38] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 8% | – | – | [39] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 35% | 65% | – | ±1.0% | [32] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% (27%) |

71% (73%) |

3% | [30] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 51% (62%) |

31% [17% support some rights] (38%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% [c] | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 52% (57%) |

40% (43%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 17% (18%) |

75% (82%) |

8% | [38] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 57% (58%) |

42% | 1% | [34] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 65% (75%) |

22% [10% support some rights] (25%) |

13% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 79% (84%) |

15% (16%) |

6% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Cadem | 2024 | 77% (82%) |

22% (18%) |

2% | ±3.6% | [40] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 43% (52%) |

39% [20% support some rights] (48%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% [c] | [41] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 46% (58%) |

33% [19% support some rights] (42%) |

21% | ±5% [c] | [33] | |

| CIEP | 2018 | 35% | 64% | 1% | [42] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) |

51% (55%) |

7% | [38] | ||

| Apretaste | 2019 | 63% | 37% | – | [43] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% (53%) |

44% (47%) |

6% | [38] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 60% | 34% | 6% | [38] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 93% | 5 | 2% | [38] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 10% | 90% | – | ±1.1% | [32] | |

| CDN 37 | 2018 | 45% | 55% | - | [44] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2019 | 23% (31%) |

51% (69%) |

26% | [45] | ||

| Universidad Francisco Gavidia | 2021 | 82.5% | – | [46] | |||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 41% (45%) |

51% (55%) |

8% | [38] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 76% (81%) |

18% (19%) |

6% | [38] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 62% (70%) |

26% [16% support some rights] (30%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 82% (85%) |

14% (15%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% (85%) |

14 (%) (15%) |

7% | [38] | ||

| Women's Initiatives Supporting Group | 2021 | 10% (12%) |

75% (88%) |

15% | [47] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (83%) |

18% [10% support some rights] (20%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 80% (82%) |

18% | 2% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% (87%) |

13%< | 3% | [38] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 48% (49%) |

49% (51%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 57% (59%) |

40% (41%) |

3% | [38] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | 88% | – | ±1.4%c | [32] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 23% | 77% | – | ±1.1% | [32] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 21% | 79% | – | ±1.3% | [39] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 5% | 95% | – | ±0.3% | [32] | |

| CID Gallup | 2018 | 17% (18%) |

75% (82%) |

8% | [48] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 58% (59%) |

40% (41%) |

2% | [34] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 44% (56%) |

35% [18% support some rights] (44%) |

21% not sure | ±5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 31% (33%) |

64% (67%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) |

52% (55%) |

6% | [38] | ||

| Gallup | 2006 | 89% | 11% | – | [49] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 53% (55%) |

43% (45%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 5% | 92% (95%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 68% (76%) |

21% [8% support some rights] (23%) |

10% | ±5%[c] | [33] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 86% (91%) |

9% | 5% | [38] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 36% (39%) |

56% (61%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 58% (66%) |

29% [19% support some rights] (33%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 73% (75%) |

25% | 2% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 69% (72%) |

27% (28%) |

4% | [38] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 16% | 84% | – | ±1.0% | [32] | |

| Kyodo News | 2023 | 64% (72%) |

25% (28%) |

11% | [50] | ||

| Asahi Shimbun | 2023 | 72% (80%) |

18% (20%) |

10% | [51] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 42% (54%) |

31% [25% support some rights] (40%) |

22% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 68% (72%) |

26% (28%) |

6% | ±2.75% | [34] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2016 | 7% (7%) |

89% (93%) |

4% | [35] [36] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 9% | 90% (91%) |

1% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) |

77% (79%) |

3% | [30] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 36% | 59% | 5% | [38] | ||

| Liechtenstein Institut | 2021 | 72% | 28% | 0% | [52] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 39% | 55% | 6% | [38] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% | 13% | 3% | [38] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 17% | 82% (83%) |

1% | [34] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 74% | 24% | 2% | [38] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 55% | 29% [16% support some rights] | 17% not sure | ±3.5%[c] | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (66%) |

32% (34%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Europa Libera Moldova | 2022 | 14% | 86% | [53] | |||

| IPSOS | 2023 | 36% (37%) |

61% (63%) |

3% | [30] | ||

| Lambda | 2017 | 28% (32%) |

60% (68%) |

12% | [54] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 77% | 15% [8% support some rights] | 8% not sure | ±5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 89% (90%) |

10% | 1% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 2% | [38] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 70% (78%) |

20% [11% support some rights] (22%) |

9% | ±3.5% | [55] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 25% | 75% | – | ±1.0% | [32] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 2% | 97% (98%) |

1% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) |

78% (80%) |

2% | [30] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 72% (79%) |

19% (21%) |

9% | [35] [36] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 22% | 78% | – | ±1.1% | [32] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 26% | 74% | – | ±0.9% | [32] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 36% |

44% [30% support some rights] | 20% | ±5% [c] | [33] | |

| SWS | 2018 | 22% (26%) |

61% (73%) |

16% | [56] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (54%) |

43% (46%) |

6% | [57] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (43%) |

54% (57%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| United Surveys by IBRiS | 2024 | 50% (55%) |

41% (45%) |

9% | [58] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% | 45% | 5% | [38] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 80% (84%) |

15% [11% support some rights] (16%) |

5% | [55] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 81% | 14% | 5% | [38] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 25% (30%) |

59% [26% support some rights] (70%) |

17% | ±3.5% | [55] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 25% | 69% | 6% | [38] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 17% (21%) |

64% [12% support some rights] (79%) |

20% not sure | ±4.8% [c] | [41] | |

| FOM | 2019 | 7% (8%) |

85% (92%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [59] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 9% | 91% | – | ±1.0% | [32] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 11% | 89% | – | ±0.9% | [32] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 4% | 96% | – | ±0.6% | [32] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 24% (25%) |

73% (75%) |

3% | [30] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 33% | 46% [21% support some rights] | 21% | ±5% [c] | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (47%) |

51% (53%) |

4% | [34] | ||

| Focus | 2024 | 36% (38%) |

60% (62%) |

4% | [60] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 37% | 56% | 7% | [38] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 62% (64%) |

37% (36%) |

2% | [38] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 53% | 32% [14% support some rights] | 13% | ±5% [c] | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 38% (39%) |

59% (61%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 36% | 37% [16% support some rights] | 27% not sure | ±5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (42%) |

56% (58%) |

3% | [34] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (80%) |

19% [13% support some rights] (21%) |

9% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 87% (90%) |

10% | 3% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 88% (91%) |

9% (10%) |

3% | [38] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 23% (25%) |

69% (75%) |

8% | [34] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 18% | – | – | [39] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 78% (84%) |

15% [8% support some rights] (16%) |

7% not sure | ±5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 92% (94%) |

6% | 2% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 1% | [38] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 54% (61%) |

34% [16% support some rights] (39%) |

13% not sure | ±3.5% | [55] | |

| CNA | 2023 | 63% | 37% | [61] | |||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (51%) |

43% (49%) |

12% | [34] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 58% | 29% [20% support some rights] | 12% not sure | ±5%[c] | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 60% (65%) |

32% (35%) |

8% | [34] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 16% | – | – | [39] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 18% (26%) |

52% [19% support some rights] (74%) |

30% not sure | ±5% [c] | [33] | |

| Rating | 2023 | 37% (47%) |

42% (53%) |

22% | ±1.5% | [62] | |

| YouGov | 2023 | 77% (84%) |

15% (16%) |

8% | [63] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 66% (73%) |

24% [11% support some rights] (27%) |

10% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 74% (77%) |

22% (23%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (62%) |

32% [14% support some rights] (39%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% | [33] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (65%) |

34% (35%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [34] | |

| LatinoBarómetro | 2023 | 78% (80%) |

20% | 2% | [64] | ||

| Equilibrium Cende | 2023 | 55% (63%) |

32% (37%) |

13% | [65] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 65% (68%) |

30% (32%) |

5% | [55] |

Adoption

[edit]| Country | Pollster | Year | For[a] | Against[a] | Neither[b] | Margin of error |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 9% | 90% | 1% | ±3.6% | [66] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 2% | 97% | 1% | ±3.6% | [67] | |

| Ipsos | 2023 | 57% (66%) |

29% [10% support some rights] (34%) |

14% | ±3.5% [c] | [66] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 38% | 58% | 4% | ±3.6% | [67] |

| Country | Pollster | Year | For | Against | Don't Know/Neutral/No answer/Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipsos | 2021 | 66%[68] | 30% | 4% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 66%[68] | 21% | 13% | |

| Midgam Institute | 2017 | 60%[69] | - | - | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 68%[68] | 20% | 13% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 24%[68] | 65% | 11% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 23%[68] | 67% | 10% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 46%[68] | 45% | 9% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 39%[68] | 44% | 18% |

| Country | Pollster | Year | For | Against | Don't Know/Neutral/No answer/Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipsos | 2023 | 71%[70] | 24% | 6% | |

| Ipsos | 2023 | 69%[70] | 22% | 9% | |

| Ipsos | 2023 | 74%[70] | 17% | 9% | |

| CADEM | 2022 | 70%[71] | 28% | 2% | |

| Ipsos | 2023 | 53%[70] | 40% | 7% | |

| Ipsos | 2023 | 60%[70] | 34% | 6% | |

| Ipsos | 2023 | 51%[70] | 42% | 7% | |

| Ipsos | 2023 | 64%[70] | 26% | 10% | |

| Equipos Consultores | 2013 | 52%[72] | 39% | 9% | |

| Equilibrium Cende | 2023 | 48%[73] (55%) |

39% (45%) |

13% |

| Country | Pollster | Year | For | Against | Don't Know/Neutral/No answer/Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 65%[74] | 30% | 5% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 72%[75] | 21% | 7% | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 12%[76] | 68%[76] | 20%[76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 10%[76] | 86%[76] | 4%[76] | |

| CVVM | 2019 | 47%[77] | 47% | 6% | |

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 75%[78] | - | - | |

| HumanrightsEE | 2023 | 47%[79] | 44%[79] | 9%[79] | |

| Taloustutkimus | 2013 | 51%[80] | 42%[80] | 7%[80] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 62%[75] | 29% | 10% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 69%[75] | 24% | 6% | |

| KAPA Research | 2023 | 53%[81] | 41%[81] | 6%[81] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 59%[75] | 36% | 5% | |

| Red C Poll | 2011 | 60%[82] | - | - | |

| Eurispes | 2023 | 50.4% [83] | 49.6% | 0% | |

| SKDS | 2023 | 27%[84] | 23%[84] | 46%[84] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 12%[76] | 82%[76] | 6%[76] | |

| Politmonitor | 2013 | 55%[85] | 44%[85] | 1%[85] | |

| Misco | 2014 | 20%[86] | 80%[86] | - | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 83%[75] | 12% | 5% | |

| YouGov | 2012 | 54%[87] | 34%[87] | 12%[87] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 33%[75] | 58% | 10% | |

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 59%[88] | 28%[88] | 13%[88] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 8%[76] | 82%[76] | 10%[76] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 23%[75] | 67% | 10% | |

| Civil Rights Defenders | 2020 | 22.5%[89] | - | - | |

| Eurobarometer | 2006 | 12%[76] | 84%[76] | 4%[76] | |

| Delo Stik | 2015 | 38%[90] | 55%[90] | 7%[90] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 77%[75] | 17% | 6% | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 79%[75] | 17% | 4% | |

| Pink Cross | 2020 | 67%[91] | 30%[91] | 3%[91] | |

| Gay Alliance of Ukraine | 2013 | 7%[92] | 68%[92] | 12% 13% would allow some exceptions[92] | |

| Ipsos | 2021 | 72%[75] | 19% | 9% |

| Country | Pollster | Year | For | Against | Don't Know/Neutral/No answer/Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipsos | 2021 | 71%[93] | 21% | 8% | |

| Research New Zealand | 2012 | 64%[94] | 31% | 5% |

Law

[edit]The legal status of homosexuality varies greatly around the world. Homosexual acts between consenting adults are known to be illegal in about 70 out of the 195 countries of the world.

Homosexual sex acts may be illegal, especially under sodomy laws, and where they are legal, the age of consent often differs from country to country. In some cases, homosexuals are prosecuted under vaguely worded "public decency" or morality laws. Some countries have special laws preventing certain public expressions of homosexuality.[95] Nations or subnational entities may have anti-discrimination legislation in place to protect against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in the workplace, housing, health services and education. Some give exemptions, allowing employers to discriminate if they are a religious organisation, or if the employee works with children.

| Same-sex intercourse illegal. Penalties: | |

Prison; death not enforced | |

Death under militias | Prison, with arrests or detention |

Prison, not enforced1 | |

| Same-sex intercourse legal. Recognition of unions: | |

Extraterritorial marriage2 | |

Limited foreign | Optional certification |

None | Restrictions of expression, not enforced |

Restrictions of association with arrests or detention | |

1No imprisonment in the past three years or moratorium on law.

2Marriage not available locally. Some jurisdictions may perform other types of partnerships.

Legal recognition of same-sex relationships also varies greatly. Legal privileges pertaining to different-sex relationships that may be extended to same-sex couples include parenting, adoption and access to reproductive technologies; immigration; spousal benefits for employees such as pensions, health funds and other services; family leave; medical rights, including hospital visitation, notification and power of attorney; inheritance when a partner dies without leaving a will; and social security and tax benefits. Same-sex couples without legal recognition may also lack access to domestic violence services, as well as mediation and arbitration over custody and property when relationships end. Some regions have laws specifically excluding same-sex couples from particular rights such as adoption.

In 2001, the Netherlands became the first country to recognize same-sex marriage. Since then same-sex marriages were subsequently recognized in Belgium (2003), Spain (2005), Canada (2005), South Africa (2006), Norway (2009), Sweden (2009), Portugal (2010), Iceland (2010), Argentina (2010), Denmark (2012), Brazil (2013), France (2013), Uruguay (2013), New Zealand (2013), Luxembourg (2015), Ireland (2015), the United States (2015), Colombia (2016), Finland (2017), Germany (2017), Australia (2017), Austria (2019), Taiwan (2019), Ecuador (2019), United Kingdom (2020), Costa Rica (2020), Chile (2022), Switzerland (2022), Slovenia (2022), Cuba (2022), Mexico (2022) and Andorra (2023). Israel, legally recognizes same-sex marriages, but does not allow such marriages to be performed within the country.

Islamic law

[edit]On the other end of the spectrum, several countries impose the death penalty for homosexual acts, per the application of some interpretations of Shari'a law. As of 2022, these include Afghanistan, Mauritania, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Yemen and northern Nigeria.[96][97]

In Saudi Arabia, the maximum punishment for homosexuality is public execution. However, the government will use other punishments – e.g., fines, jail time, and whipping – as alternatives, unless it feels that homosexuals are challenging state authority by engaging in LGBT social movements.[98]

Most international human rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, condemn laws that make homosexual relations between consenting adults a crime. Since 1994, the United Nations Human Rights Committee has also ruled that such laws violate the right to privacy guaranteed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Of the nations with a majority of Muslim inhabitants, many, even those with secular constitutions, continue to outlaw homosexuality, though only in a minority (Yemen[99] and Afghanistan[100]) is it punishable by death. Of the countries where homosexuality is illegal, only Lebanon has an internal effort to legalize it.[101] Muslim-majority countries where homosexuality is not criminalized include Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey, Kosovo and others.

Religion

[edit]As with social attitudes in general, religious attitudes towards homosexuality vary between and among religions and their adherents. Traditionalists among the world's major religions generally disapprove of homosexuality, and prominent opponents of social acceptance of homosexuality often cite religious arguments to support their views. Liberal currents also exist within most religions, and modern lesbian and gay scholars of religion sometimes point to a place for homosexuality among historical traditions and scriptures, and emphasise religious teachings of compassion and love.

Abrahamic religions such as Judaism, Islam, and various denominations of Christianity traditionally forbid sexual relations between people of the same sex and teach that such behaviour is sinful. Religious authorities point to passages in the Qur'an,[102] the Old Testament[103] and the New Testament[104] for scriptural justification of these beliefs.

Among the Sinic religions of East Asia, including Confucianism, Chinese folk religion and Taoism, passionate homosexual expression is usually discouraged because it is believed to not lead to human fulfillment.[105]

Corporate attitudes

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2013) |

In some capitalist countries, large private sector firms often lead the way in the equal treatment of gay men and lesbians. For instance, more than half of the Fortune 500 offer domestic partnership benefits and 49 of the Fortune 50 companies include sexual orientation in their non-discrimination policies (only ExxonMobil does not).[106][107] At the same time, studies show that many private firms engage in significant employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. In one study, for example, two fictitious but realistic resumes were sent to roughly 1,700 entry-level job openings. The two resumes were very similar in terms of the applicant's qualifications, but one resume for each opening mentioned that the applicant had been part of a gay organization in college. The results showed that applicants without the gay signal had an 11.5 percent chance of being called for an interview; openly gay applicants had only a 7.2 percent chance. The callback gap varied widely according to the location of the job. Most of the overall gap detected in the study was driven by the Southern and Midwestern states in the sample—Texas, Florida, and Ohio. The Western and Northeastern states in the sample (California, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and New York) had only small and statistically insignificant callback gaps.[108]

In the Western world, in particular the United States and the United Kingdom, the corporatisation of LGBT pride parades has been criticised by some.[109][110]

Anti-homosexual attitudes

[edit]

Conservatism

[edit]Conservatism is a term broadly used for people who are inclined to traditional values.

While conservatism includes people of many views, a significant proportion of its adherents consider homosexuals, and especially the efforts of homosexuals to achieve certain rights and recognition, to be a threat to valued traditions, institutions and freedoms. Such attitudes are generally tied in with opposition to what some conservatives call the "homosexual agenda".[111]

The finding that attitudes to alternative sexualities correlate strongly with nature of contact and with personal beliefs is stated in a variety of research over a substantial time period, and conservative men and women stand out in their views specifically.

Thus Herek, who established the Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men Scale in psychology, states:[112]

The ATLG and its subscales are consistently correlated with other theoretically relevant constructs. Higher scores (more negative attitudes) correlate significantly with high religiosity, lack of contact with gay men and lesbians, adherence to traditional sex-role attitudes, belief in a traditional family ideology, and high levels of dogmatism

and that:[113]

The strongest predictor of positive attitudes toward homosexuals was that the interviewee knew a gay man or lesbian. The correlation held across each demographic subset represented in the survey—sex, education level, age—bar one: political persuasion.

An example of conservative views can also be found in the discussion of what conservatives call "homosexual recruitment", within a document released by the conservative Christian organization Alliance Defense Fund states:[114]

The homosexual activist movement are driving an agenda that will severely limit the ability to live and practice the Gospel, whether it is in the boardroom, the classroom, halls of government, private organizations, and even in places of worship. In their relentless attempts to obtain special rights, that no other special interest group has, they are in the process of redefining the family, demanding not only 'tolerance' ... but 'acceptance', and ultimately seeking to marginalize, censor, and punish those individuals who stand in the way of their multiple goals.

As this statement illustrates, those who believe that a disapproving attitude toward homosexuality is a tenet of their religion can see efforts to abolish such attitudes as an attack on their religious freedom. Those who regard homosexuality as a sin or perversion can believe that acceptance of homosexual parents and same-sex marriage will redefine and diminish the institutions of family and marriage.

More generally, conservatives—by definition—prefer that institutions, traditions and values remain unchanged, and this has put many of them in opposition to efforts designed to increase the cultural acceptance and legal rights of homosexuals[citation needed].

Psychology and sexual orientation

[edit]In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association's board of trustees voted to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).[115] Though some criticized this as a political decision, the social and political impetus for change was supported by scientific evidence.[116] In fact, the research of Evelyn Hooker and other psychologists and psychiatrists helped to end the notion that homosexuality was in and of itself a mental illness. Homosexuality in and of itself was removed from the DSM in 1974, but a diagnosis of distress related to one's sexual orientation remained in the manual until 2013 (DSM-5). In parallel fashion, the World Health Organization removed homosexuality from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) in the tenth edition of that manual in 1992 (ICD-10), but retained a diagnosis of distress related to one's sexual orientation until 2019 (ICD-11). Diagnosing a person with a medical or mental health condition on the basis of sexual orientation is no longer allowable under either of these leading diagnostic manuals.

Many religious groups and other advocates, like National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH), believe that they can "heal" or "cure" homosexuality through conversion therapy or other methods to change sexual orientation. In a survey of 882 people who were undergoing conversion therapy, attending "ex-gay" groups or "ex-gay" conferences, 22.9% reported they had not undergone any changes, 42.7% reported some changes, and 34.3% reported much change in sexual orientation.[117] Many Western health and mental health professional organizations believe sexual orientation develops across a person's lifetime,[118] but that this therapy is unnecessary, potentially harmful, and the effectiveness has not been rigorously and scientifically proven. Much attention was given to the dissent from this opinion by Robert Spitzer, but he later realized that his research was flawed and apologized for the damage it may have done.[119] Another study refuting the claims of conversion therapy proponents was done in 2001 by Ariel Shidlo and Michael Schroeder, which showed only 3% of the participants claiming to have completely changed their orientation from gay to straight.[120]

In many non-Western post-colonial countries, homosexual orientation is still considered to be a mental disorder and illness. In Muslim areas, this position is ascribed to the earlier adoption of European Victorian attitudes by the westernized elite, in areas where previously native traditions embraced same-sex relations.[121]

Blame for plagues and disasters

[edit]The destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah as takes place in the Bible is sometimes attributed to attempted homosexual rape, but this is disputed[122] and differs from earlier beliefs. Early Jewish belief (and some Jews today)[123] variously attributed the destruction to turning a blind eye to social injustice or lack of hospitality.[123]

Since the Middle Ages, sodomites were blamed for "bringing down the wrath of God" upon the land, and their pleasures blamed for the periodic epidemics of disease which decimated the population. This "pollution" was thought to be cleansed by fire, as a result of which countless individuals were burned at the stake or run through with white-hot iron rods.[citation needed]

Since the end of the 1980s similar accusations have been made, inspired by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with preachers such as Jerry Falwell blaming both the victim and a supposedly tolerant societal view of homosexuality.[124] Recent researches indicate that in the years since, the epidemic has spread and now has many more heterosexual victims than homosexual.[125]

Association with child sexual abuse and pedophilia

[edit]Some people fear exposing their children to homosexuals in unsupervised settings because they believe the children might be molested, raped, or "recruited" to be homosexuals themselves.[126][127][128] The publicity surrounding the Roman Catholic sex abuse cases has heightened these concerns.[129] Many organizations focus on these concerns, drawing connections between homosexuality and pedophilia. According to the John Jay Report, a study commissioned by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops[130] under the auspices of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and an all-lay review board headed by Illinois Appellate Court Justice Anne M. Burke, "81% of the reported victims of child sexual abuse by Catholic clergy were boys." The review board went on to conclude that, "the crisis was characterized by homosexual behavior", and in light of this, "the current crisis cannot be addressed without consideration of issues related to homosexuality." According to Margaret Smith, one of John Jay's researchers, however, it is "an unwarranted conclusion" to assert that the majority of priests who abused male victims are gay. Though "the majority of the abusive acts were homosexual in nature ... participation in homosexual acts is not the same as sexual identity as a gay man."[131] Psychology professor Gregory Herek also analyzed a number of studies and found no relationship between sexual orientation and molestation.[132] One of her fellow researchers, Louis Schlesinger, argued that the main problem was pedophilia or ephebophilia, not sexual orientation and said that some men who are married to adult women are attracted to adolescent males.[133]

Small-scale studies by Carole Jenny, A.W. Richard Sipe, and others have not found evidence that homosexuals are more likely to molest children than heterosexuals.[134][135][136] Based on the responses of a sample of thousands of admitted child molesters, one study found that 70% of the sex offenders who targeted boys rated themselves as predominantly or exclusively heterosexual in adult orientation on the Kinsey scale, and only 8% as exclusively homosexual.[137] Phallometric testing on community males shows that men with a preference for adult males (often called "androphiles" in these studies) are no more attracted to adolescent or younger boys than are men with a preference for adult females (or "gynephiles").[138][139][140] Conversely, sex offenders targeting boys—especially prepubescent boys—may be heterosexual, while others lack attraction to adults of either sex.[141] Kurt Freund, analyzing sex offender samples, concluded that only rarely does a sex offender against male children have a preference for adult males;[139] Frenzel and Lang (1989) also noticed a lack of androphiles in their phallometric analysis of 144 child sex offenders, which included 25 men who offended against underage boys.[142] A study involving 21 adult sex offenders against boys found that two thirds of them had a sexual preference for women over men, as measured by the penile plethysmograph, with the larger, "heterosexual" subgroup targeting younger boys than the "homosexual" group.[143] A more recent survey, which asked self-identified pedophiles in online communities to rate their sexual attraction to males and females from age 1 to age 18, found that those men disclosed very low levels of attraction towards more mature males, with the authors concluding that, "[i]ntense sexual attraction to male children is distinct from, and not generally compatible with, intense sexual attraction to men."[144]

Johns Hopkins University psychiatrist Frederick Berlin, who runs a treatment program for offenders, says it is flawed to assume that men who molest young boys are attracted to adult men; Berlin defines attraction to children as a separate orientation of its own.[145] Psychotherapist A. W. Richard Sipe also argues that the sexual deprivation that occurs in the priesthood could lead one to turn to children and that boys are more accessible to priests and other male authority figures than girls.[135] A study by A. Nicholas Groth found that nearly half of the child sex offenders in his small sample were exclusively attracted to children. The other half regressed to children after finding trouble in adult relationships. No one in his sample was primarily attracted to same-sex adults.[146]

The empirical research shows that sexual orientation does not affect the likelihood that people will abuse children.[147][148][149] Many child molesters cannot be characterized as having an adult sexual orientation at all; they are fixated on children.[147]

Lawmakers and social commentators have sometimes expressed a concern that normalizing homosexuality would also lead to normalizing pedophilia, if it were determined that pedophilia too were a sexual orientation.[150]

International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association

Opposition to "promotion of homosexuality"

[edit]"Promotion of homosexuality"[151] is a group of behaviors believed by some gay-rights opponents to be carried out in the mass media,[152] public places,[153] etc. The term gay propaganda may be used by others to allege similar behaviors, especially in relation to false accusations of homosexual recruitment and an alleged "gay agenda".[citation needed]

In the United Kingdom, Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act banned "promotion of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship" by local government employees in the course of their duties. The act was aimed to prevent the "promotion of homosexuality" in schools. Prosecutions increased following the act.[154] Section 28 was later repealed in Scotland on 21 June 2000 as one of the first pieces of legislation enacted by the new Scottish Parliament, and on 18 November 2003 in England and Wales by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003, with the Labour government also issuing an apology to LGBT people for the act.[155] ()

Lithuania put in place a similar such ban 16 June 2009 amid protests by gay rights groups. LGBT rights groups stated that it would be taken to the European Court of Human Rights for violation of European Human rights laws.[158] Several Russian territories had implemented similar laws restricting the distribution of "propaganda" promoting homosexuality to minors, including Ryazan, Arkhangelsk, and Saint Petersburg.[159] In June 2013, a federal bill was passed in Russia that made the distribution of materials promoting "non-traditional sexual relationships" among minors a criminal offence; the bill's author Yelena Mizulina argued that the law was intended to help protect "traditional family values".[160][161]

Violence

[edit]Gay people have been the target of violence for their sexuality in various cultures throughout history. During the Holocaust, 100,000 gay men were arrested, and between 5,000 and 15,000 gay men perished in Nazi concentration camps.[162] Violence against LGBT people continues to occur today, fueled by anti-gay rhetoric.[163]

Homophobic rhetoric

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2018) |

Regions and historical periods

[edit]Societal attitudes toward homosexuality vary greatly in different cultures and different historical periods, as do attitudes toward sexual desire, activity and relationships in general. All cultures have their own values regarding appropriate and inappropriate sexuality; some sanction same-sex love and sexuality, while others disapprove of such activities.[164] As with heterosexual behaviour, different sets of prescriptions and proscriptions may be given to individuals according to their gender, age, social status or class. For example, among the samurai class of pre-modern Japan, it was recommended for a teenage novice to enter into an erotic relationship with an older warrior (see Shudo), but sexual relations between the two became inappropriate once the boy came of age.[165]

Ancient India

[edit]Ancient Greece

[edit]

In Ancient Greece homoerotic practices were widely present, and integrated into the religion, education, philosophy and military culture.[166] The sexualized form of these relationships was the topic of vigorous debate. In particular, anal intercourse was condemned by many, including Plato, as a form of hubris and faulted for dishonoring and feminizing the boys. Relations between adult males were generally ridiculed. Plato also believed that the chaste form of the relationship was the mark of an enlightened society, while only barbarians condemned it.[167]

The extent to which the Greeks engaged in and tolerated homosexual relations is open to some debate. In Sparta and Thebes, there appeared to be a particularly strong emphasis on these relationships, and it was considered an important part of a youth's education.[168]

Ancient Rome

[edit]"Homosexual" and "heterosexual" were not categories of Roman sexuality, and Latin lacks words that would translate these concepts exactly.[169] The primary dichotomy of Roman sexuality was active/dominant/masculine and passive/submissive/"feminized". The masculinity of an adult male citizen was defined sexually by his taking the penetrative role, whether his partner was female or a male of lower status.[170] A Roman citizen's political liberty (libertas) was defined in part by the right to preserve his body from physical compulsion or use by others;[171] for the male citizen to use his body to give pleasure was considered servile and subversive of the social hierarchy.[172]

It was acceptable for a man to be attracted to a beautiful young male,[173] but the bodies of citizen youths were strictly off-limits.[174] Acceptable male partners were slaves, male prostitutes, or others who lacked social standing (the infames). Same-sex relations among male citizens of equal status, including soldiers, were disparaged, and in some circumstances penalized harshly.[175] In political rhetoric, a man might be attacked for effeminacy or playing the passive role in sex acts, but not for performing penetrative sex on a socially acceptable male partner.[176] Threats of anal or oral rape against another man were forms of masculine braggadocio.[177]

Homosexual behaviors were regulated in so far as they threatened or impinged on an ideal of liberty for the dominant male, who retained his masculinity by not being penetrated.[178] The Lex Scantinia imposed penalties on those who committed a sex crime (stuprum) against a freeborn male minor; it may also have been used to prosecute adult male citizens who willingly took the "passive" role.[179] Children who were born into slavery or became enslaved had no legal protections against sexual abuse; a good-looking and graceful slave-boy might be chosen and groomed as his owner's sexual favorite.[180] Pederasty in ancient Rome thus differed from pederastic practice in ancient Greece, where by custom the couple were both freeborn males of equal social status.

Although Roman law did not recognize marriage between men, and in general Romans regarded marriage as a heterosexual union with the primary purpose of producing children, in the early Imperial period some male couples were celebrating traditional marriage rites. Juvenal remarks that his friends often attended such ceremonies.[181] The emperor Nero had two marriages to men, once as the bride (with a freedman Pythagoras) and once as the groom. He had his pederastic lover Sporus castrated, and during their marriage, Sporus appeared in public as Nero's wife wearing the regalia that was customary for Roman empresses.[182]

Same-sex relations among women are infrequently documented during the Republic and Principate, but better attested during the Empire.[183] An early reference to homosexual women as "lesbians" is found in the Roman-era Greek writer Lucian (2nd century AD): "They say there are women like that in Lesbos, masculine-looking, but they don't want to give it up for men. Instead, they consort with women, just like men."[184] Since male writers thought a sex act required an active or dominant partner who was "phallic", they imagined that in lesbian sex one of the women would use a dildo or have an exceptionally large clitoris for penetration, and that she would be the one experiencing pleasure.[185] The poet Martial describes lesbians as having outsized sexual appetites and performing penetrative sex on both women and boys.[186] Satiric portrayals of women who sodomize boys, drink and eat like men, and engage in vigorous physical regimens, may reflect cultural anxieties about the growing independence of Roman women.[187]

Ancient China

[edit]Some early Chinese emperors are speculated to have had homosexual relationships, accompanied by heterosexual ones.[188] Same-sex practices have been documented there since the "Spring and Autumn Annals" period (parallel with Classical Greece) and its roots are found in the legend of China's origin, the reign of the Yellow Emperor, who, among his many inventions, is credited with being the first to take male bedmates.[citation needed]

Opposition to homosexuality in China originates in the medieval Tang dynasty, attributed to the rising influence of Christian and Islamic values,[189] but did not become fully established until the late Qing dynasty and the Republic of China.[190] The Chinese Psychiatrists' Association removed homosexuality from the list of mental illnesses in April 2001.[191][192] However, as openly gay scriptwriter and teacher Cui Zi'en points out, "In the West, it's frowned on to criticize homosexuals and even more to make them feel different", says Cui Zi'en, contrasting it with Chinese society which, "is changing, but there'll always be people who'll feel disgust".[193]

Ancient Israel

[edit]In the book of Leviticus, intercourse between males was condemned as an 'abomination' (Leviticus 18:22, 22:13), and required the death penalty for those men who "lie with a man as with a woman".[194]

Early Christianity

[edit]Many contend that from its earliest days, Christianity followed the Hebrew tradition of condemnation of male sexual intercourse and certain forms of sexual relations between men and women, labeling both as sodomy. Some contemporary Christian scholars dispute this however. The teachings of Jesus Christ encouraged a turning away from and forgiveness of sin, including those sins of sexual impurity, although Jesus never referred to homosexuality specifically. Jesus was known as a defender of those whose sexual sins were condemned by the Pharisees. At the same time, Jesus strongly upheld the Ten Commandments and urged those whose sexual sins were forgiven to, "go, and sin no more".[195]

Saint Paul was even more explicit in his condemnation of sinful behavior, including sodomy, saying, "Know you not that the unjust shall not possess the kingdom of God? Do not err: neither fornicators, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor the effeminate, nor liers with mankind, nor thieves, nor covetous, nor drunkards, nor railers, nor extortioners, shall possess the kingdom of God."[196] However, the exact meanings of two of the ancient Greek words that Paul used that supposedly refer to homosexuality are disputed among scholars. In the Septuagint translation of the Old Testament, however, the relevant words employed in 1 Corinthians and 1 Timothy are the same words employed in Leviticus 18 to denote gay men.

Christian Roman Empire / Byzantine Empire

[edit]After the emperor Constantine ended the persecution of Christians throughout the Roman Empire and Theodosius made Christianity the official state religion in the 4th century, Christian attitudes toward sexual behavior were soon incorporated into Roman Law. In the year 528, the emperor Justinian I, responding to an outbreak of pederasty among the Christian clergy, issued a law which made castration the punishment for sodomy.[197]

Medieval Europe

[edit]In medieval Europe, homosexuality was considered sodomy and was punishable by death. Persecutions reached their height during the Medieval Inquisitions, when the sects of Cathars and Waldensians were accused of fornication and sodomy, alongside accusations of Satanism. In 1307, accusations of sodomy and homosexuality were major charges leveled during the Trial of the Knights Templar.[198] The theologian Thomas Aquinas was influential in linking condemnations of homosexuality with the idea of natural law, arguing that "special sins are against nature, as, for instance, those that run counter to the intercourse of male and female natural to animals, and so are peculiarly qualified as unnatural vices".[199]

New Guinea

[edit]The Bedamini people of New Guinea believe that semen is the main source of masculinity and strength. In consequence, the sharing of semen between men, particularly when there is an age gap, is seen as promoting growth throughout nature, while excessive heterosexual activities are seen as leading to decay and death.[200]

Russia

[edit]A survey run by the Levada Centre in Russia in July 2010 concluded that "homophobia is widespread in Russian society". It draws this conclusion from the following findings. 74% of respondents believed that gays and lesbians are immoral or psychologically disturbed people. Only 15% responded that homosexuality is as legitimate as traditionally conceived sexual orientation. 39% consider that they should be compulsorily treated or alternatively isolated from society. 4% considered that it is necessary to liquidate people of a non-traditional sexual orientation.

On the other hand, many Russians (45%) were in favour of the equality of homosexuals with other citizens (41% against, 15% undecided). Most supported the introduction in Russia of laws forbidding discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and incitement of hatred for gays and lesbians (31% against, 28% undecided).

The Levada Centre reached the following conclusions on the distribution of these view in different groups of society. "In Russian society, homophobia is most often encountered among men, older respondents (over 55), and people with an average level of education and low income... Women, young Russians (18–39), and well educated and comfortably off respondents showed more tolerance for people of a non-traditional sexual orientation, and more understanding of related issues. Respondents over 40, people of average or lower education or low incomes, and rural people—the sectors retaining the inertia of Soviet thinking—are more likely to believe that homosexuality is a disease requiring treatment, and that homosexuals must be isolated from society".[201]

Arab world

[edit]Men who have sex with other men in Arab societies do not commonly refer to each other as homosexuals. Laurens Buijs, Gert Hekma, and Jan Willem Duyvendak, authors of the 2011 article "'As long as they keep away from me': The paradox of antigay violence in a gay-friendly country", said "This might explain why they are more likely to condemn men who explicitly claim a homosexual identity.[202] In the 2011 article they said that among men in Arab countries who do not identify as homosexual, anal sexual intercourse is "often said to be common" and that the men's "masculine gender role is not at stake as long as they take up the active role".[202]

Netherlands

[edit]Laurens Buijs, Gert Hekma, and Jan Willem Duyvendak, authors of the 2011 article "'As long as they keep away from me': The paradox of antigay violence in a gay-friendly country", said that the Netherlands has a "tolerant and gay-friendly image",[203] and that Dutch people, according to cross-national survey research, exhibit more acceptance of homosexuality than "most other European peoples".[204] They also stated that Dutch people exhibit support for equal rights for and non-discrimination of homosexuals.[204] They explained "Amsterdam, in particular is often associated with gay emancipation, as it provided the setting for the world's first legally recognized 'gay marriage' in 2001, and hosts the famous gay parade with festively decorated boats floating through the city's picturesque canals each year."[204] According to the article, despite this reputation, the aspects of attempts of men to seduce other men, anal sex, behavior perceived as "feminine" from males, and public displays of affection among homosexuals are likely to trigger homophobia in the Netherlands.[205]

They argued that "antigay violence is a remarkably grave problem" in that country.[203] They explained that members of five ethnic groups, Dutch-Antilleans, Dutch-Greeks, Dutch-Moroccans, Dutch-Serbs, Dutch-Turks, "are less accepting towards homosexuality, also when controlled for gender, age, level of education and religiosity".[206] They also stated that the culture in the Armed Forces of the Netherlands "is notoriously masculine and intolerant towards homosexuality".[206] Until the year 2000, right wing politicians in the Netherlands generally opposed homosexuality, but as of 2011 show support of homosexuality and oppose anti-gay attitudes in immigrant groups, stating that the country has a "Dutch tradition of tolerance" for homosexuality.[203]

United States

[edit]McCarthy era

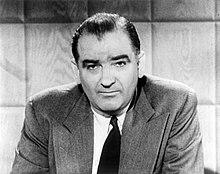

[edit]

In the 1950s in the United States, open homosexuality was taboo. Legislatures in every state had passed laws against homosexual behavior well before this, most notably anti-sodomy laws. Many politicians treated the homosexual as a symbol of antinationalism, construing masculinity as patriotism and marking the "unmasculine" homosexual as a threat to national security. This perceived connection between homosexuality and antinationalism was present in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia[207] as well, and appears in contemporary politics to this day.[208][209]

Senator Joseph McCarthy used accusations of homosexuality as a smear tactic in his anti-Communist crusade, often combining the Second Red Scare with the Lavender Scare. On one occasion, he went so far as to announce to reporters, "If you want to be against McCarthy, boys, you've got to be either a Communist or a cocksucker."[210]

Senator Kenneth Wherry likewise attempted to invoke some connection between homosexuality and antinationalism as, for example, when he said in an interview with Max Lerner that "You can't hardly separate homosexuals from subversives." Later in that same interview he draws the line between patriotic Americans and gay men: "But look Lerner, we're both Americans, aren't we? I say, let's get these fellows [closeted gay men in government positions] out of the government."[211]

There were other perceived connections between homosexuality and Communism. Wherry publicized fears that Joseph Stalin had obtained a list of closeted homosexuals in positions of power from Adolf Hitler, which he believed Stalin intended to use to blackmail these men into working against the U.S. for the Soviet regime.[212] The 1950 Senate subcommittee Hoey Report "Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government" said that "the pervert is easy prey to the blackmailer.... It is an accepted fact among intelligence agencies that espionage organizations the world over consider sex perverts who are in possession of or have access to confidential material to be prime targets where pressure can be exerted." Along with that security-based concern, the report found homosexuals unsuitable for government employment because "those who engage in overt acts of perversion lack the emotional stability of normal persons. In addition there is an abundance of evidence to sustain the conclusion that indulgence in acts of sex perversion weakens the moral fiber of an individual to a degree that he is not suitable for a position of responsibility."[213] McCarthy and Roy Cohn used the secrets of closeted gay American politicians as tools for blackmail more often than did foreign powers.[214]

LGBT civil rights movement

[edit]Beginning in the 20th century, LGBT rights movements have led to changes in social acceptance and in the media portrayal of same-gender relationships. The legalization of same-sex marriage, a major goal of gay rights supporters, was achieved across all fifty states during the period from 2004 to 2015. (See also LGBT rights organization.)

Attitudes toward homosexuality have changed in developed societies in the latter part of the 20th century, accompanied by a greater acceptance of gay people into both secular and religious institutions.

Some opponents of the movement say the term LGBT civil rights is a misnomer and an attempt to piggyback on the civil rights movement.[citation needed] Rev. Jesse Lee Peterson, for example, called the comparison of the civil rights movement to the "gay rights movement" a "disgrace to a black American". He said that "homosexuality is not a civil right. What we have is a bunch of radical homosexuals trying to attach their agenda to the struggles of the 1960s,"[215] while Jesse Jackson has said "Gays were never called three-fifths human in the Constitution." Gene Rivers, a Boston minister, has accused gays of "pimping" the civil rights movement.[216][failed verification]

In contrast, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a leading organization during the civil rights movement, has made clear their support for LGBT rights and equate it with other human rights and civil rights movements.[217]

Statistics

[edit]73% of the general public in the United States in 2001 stated that they knew someone who is gay, lesbian, or bisexual.[218] This is the result of a steady increase from 1983 when there were 24%, 43% in 1993, 55% in 1998, or 62% in 2000. The percentage of the general public who say there is more acceptance of LGB people in 2001 than before was 64%. Acceptance was measured on many different levels—87% of the general public would shop at a store owned by someone who is gay or lesbian but only 46% of the general public would attend a church or synagogue where a minister or rabbi is openly gay or lesbian. A 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center showed that 60% of U.S. adults think homosexuality should be accepted.[219] Males and people over 65 years old are more likely to think it is wrong. Among people who do not know someone who is LGB, 61% think the behavior is wrong. Broken down by religion, 60% of evangelical Christians think that it is wrong, whereas 11% with no religious affiliation are against it. 57% of the general public think that gays and lesbians experience a lot of prejudice and discrimination, making it the group most believed to experience prejudice and discrimination. African Americans come in second at 42%.[220]

In terms of support of public policies, according to the same 2001 study, 76% of the general public thought that there should be laws to protect gay and lesbian people from job discrimination, 74% from housing discrimination, 73% for inheritance rights, 70% support health and other employee benefits for domestic partners, 68% supported social security benefits, and 56% supported GL people openly serving in the military. 73% favored sexual orientation being included in the hate crimes statutes. 39% supported same-sex marriage, while 47% supported civil unions, and 46% supported adoption rights. A poll conducted in 2013 showed a record high of 58% of the American people supporting legal recognition for same-sex marriage.[221][222] A separate study shows that, in the United States, the younger generation is more supportive of gay rights than average, and that there is growing support for LBGT rights. In 2011, for the first time, a majority of Americans supported the legalization of same-sex marriage.[223] In 2012, President Barack Obama voiced support for gay marriage, and in the November elections, three states voted to legalize gay marriage at the ballot box for the first time in history[224] while an attempt to restrict same-sex marriage was rejected. In 2016, 55% of U.S. citizens supported same sex marriage and 37% opposed.[225]

See also

[edit]- Biphobia

- Decriminalization of homosexuality

- Gay bashing

- Heterosexism

- Homosexuality in society

- LGBT stereotypes

- Liberal homophobia

- Media portrayal of bisexuality

- Structural abuse

- Sociology of gender

- Status of same-sex marriage

Further reading

[edit]- David Ekstam. 2021. "The Liberalization of American Attitudes to Homosexuality and the Impact of Age, Period, and Cohort Effects." Social Forces.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Murray, Stephen O. (2000). Homosexualities. University of Chicago.

- ^ Crompton, Louis (2003). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674011977.

- ^ Seth Faison (2 September 1997). "Door to Tolerance Opens Partway As Gay Life Is Emerging in China". The New York Times. p. A8. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Adamczyk, Amy (2017). Cross-National Public Opinion about Homosexuality: Examining Attitudes across the Globe. University of California Press. pp. 3–7. ISBN 9780520963597.

- ^ "The Global Divide on Homosexuality" (PDF). Pew Research Center. 4 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ Graham, Sharyn, Sulawesi's fifth gender Archived 18 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Inside Indonesia, April–June 2001.

- ^ Herdt G., Sambia: Ritual and Gender in New Guinea. New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1987

- ^ Leila J. Rupp, "Toward a Global History of Same-Sex Sexuality", Journal of the History of Sexuality 10 (April 2001): 287–302.

- ^ Katz, Jonathan Ned, The Invention of Heterosexuality Plume, 1996

- ^ Andrews, Walter and Kalpakli, Mehmet, The Age of Beloveds: Love and the Beloved in Early Modern Ottoman and European Culture and Society Duke University Press, 2005 pp. 11–12

- ^ Norton, Rictor (2016). Myth of the Modern Homosexual. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781474286923. The author has made adapted and expanded portions of this book available online as A Critique of Social Constructionism and Postmodern Queer Theory.

- ^ Boswell, John (1989). "Revolutions, Universals, and Sexual Categories". In Duberman, Martin Bauml; Vicinus, Martha; Chauncey, George Jr. (eds.). Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. Penguin Books. pp. 17–36. S2CID 34904667.

- ^ Ford, C. S. & Beach, F. A. (1951). Patterns of Sexual Behavior. New York: Harper and Row.

- ^

Studies finding that heterosexual men usually exhibit more hostile attitudes toward gay men and lesbians than do heterosexual women:

- Herek, G. M. (1994). "Assessing heterosexuals' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men". In B. Greene and G. M. Herek (Eds.) Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay issues: Vol. 1 Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Thousands Oaks, California: Sage.

- Kite, M. E. (1984). "Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexuals: A meta-analytic review". Journal of Homosexuality. 10 (1–2): 69–81. doi:10.1300/j082v10n01_05. PMID 6394648.

- Morin, S.; Garfinkle, E. (1978). "Male homophobia". Journal of Social Issues. 34 (1): 29–47. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1978.tb02539.x.

- Thompson, E.; Grisanti, C.; Pleck, J. (1985). "Attitudes toward the male role and their correlates". Sex Roles. 13 (7/8): 413–427. doi:10.1007/bf00287952. S2CID 145377137.

- Larson; et al. (1980). "Heterosexuals' Attitudes Toward Homosexuality". The Journal of Sex Research. 16 (3): 245–257. doi:10.1080/00224498009551081.

- Herek, G (1988). "Heterosexuals' Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men". The Journal of Sex Research. 25 (4): 451–477. doi:10.1080/00224498809551476.

- Kite, M. E.; Deaux, K. (1986). "Attitudes toward homosexuality: Assessment and behavioral consequences". Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 7 (2): 137–162. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0702_4.

- Haddock, G.; Zanna, M. P.; Esses, V. M. (1993). "Assessing the structure of prejudicial attitudes: The case of attitudes toward homosexuals". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 65 (6): 1105–1118. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1105.

- ^ Herek, G. M. (1991). "Stigma, prejudice, and violence against lesbians and gay men". In: J. Gonsiorek & J. Weinrich (Eds.), Homosexuality: Research implications for public policy (pp. 60–80). Newbury Park, California: Sage.

- ^ a b Kyes, K. B.; Tumbelaka, L. (1994). "Comparison of Indonesian and American college students' attitudes toward homosexuality". Psychological Reports. 74 (1): 227–237. doi:10.2466/pr0.1994.74.1.227. PMID 8153216. S2CID 35037582.

- ^ Kite, M. E. (1984). "Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexuals: A meta-analytic review". Journal of Homosexuality. 10 (1–2): 69–81. doi:10.1300/j082v10n01_05. PMID 6394648.

- ^ Millham, J.; San Miguel, C. L.; Kellogg, R. (1976). "A factor-analytic conceptualization of attitudes toward male and female homosexuals". Journal of Homosexuality. 2 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1300/j082v02n01_01. PMID 1018107.

- ^ Herek, G. M. (1984). "Beyond 'homophobia': A social psychological perspective on attitudes toward lesbians and gay men". Journal of Homosexuality. 10 (1/2): 1–21. doi:10.1300/j082v10n01_01. PMID 6084028.

- ^ Commonly used scales include those designed by Herek, G. (1988), Larson et al. (1980), Kite, M. E., & Deaux, K. (1986), and Haddock et al. (1993)

- ^ Janell L. Carroll. Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Wadsworth Publishing.

- ^ "New Poll Shows Dramatic Shifts in Public Opinion of Gay Marriage Post-Obama Announcement". Atlanta Black Star. 24 May 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Kobi Nahshoni (7 July 2007). "Most Israelis would accept a gay child". Ynetnews.

- ^ Ho, Spencer (15 December 2013). "Poll: 70% of Israelis support recognition for gays". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ Herek, Gregory M. Heterosexuals' attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States, Journal of Sex Research, Nov, 2002. online Archived 11 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ *Ochs, R. (1996). "Biphobia: It goes more than two ways". In: B. A. Firestein (Ed.), Bisexuality: The psychology and politics of an invisible minority (pp. 217–239). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage

- Rust, P. C. (2000). "Bisexuality: A contemporary paradox for women". Journal of Social Issues. 56 (2): 205–221. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00161.

- Weinberg, M. S., Williams, C. J., & Pryor, D. W. (1994). Dual attraction: Understanding bisexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mohr, J. J.; Rochlen, A. B. (1999). "Measuring attitudes regarding bisexuality in lesbian, gay male, and heterosexual populations". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 46 (3): 353–369. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.46.3.353.

- ^ *Paul, J. P., & Nichols, M. (1988). "'Biphobia' and the construction of a bisexual identity". In: M. Shernoff & W. Scott (Eds.), The sourcebook on lesbian/gay health care (pp. 142–147). Washington, DC: National Lesbian and Gay Health Foundation.

- Ochs, R. (1996). "Biphobia: It goes more than two ways". In: B. A. Firestein (Ed.), Bisexuality: The psychology and politics of an invisible minority (pp. 217–239). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage

- Weinberg, M. S., Williams, C. J., & Pryor, D. W. (1994). Dual attraction: Understanding bisexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Herek, Gillis, and Cogan (1999) found that 15% of bisexual women (n = 190) and 27% of bisexual men (n = 191) had experienced a crime against their person or property because of their sexual orientation. compared to 19% of lesbians (n = 980) and 28% of gay men (n = 898). (Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (1999). Psychological sequelae of hate crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 945–951.)

- Note: the Kaiser Family Foundation (2001) found that bisexuals reported experiencing less prejudice and discrimination, while a 1997 study of heterosexual U.S undergraduate students found that they had more negative attitudes toward bisexuals than towards lesbians and gays. Kaiser Family Foundation (2001), Inside-out: A report on the experiences of lesbians, gays, and bisexuals in America and the public's view on issues and politics related to sexual orientation. http://www.kff.org ; Eliason, M. J. (1997). "The prevalence and nature of biphobia in heterosexual undergraduate students". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 26 (3): 317–326. doi:10.1023/A:1024527032040. PMID 9146816. S2CID 30800831.

- ^ "Plurality of Delaware Supports Marriage Equality". Delaware Liberal. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ^ "Delaware same-sex partnership support" (PDF). Delaware same-sex partnership. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "Attitudes towards LGBTIQ+ people in the Western Balkans" (PDF). ERA – LGBTI Equal Rights Association for the Western Balkans and Turke. June 2023.

- ^ "Un 70% d'andorrans aprova el matrimoni homosexual". Diari d'Andorra (in Catalan). 7 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Cultura polítical de la democracia en la República Dominicana y en las Américas, 2016/17" (PDF). Vanderbilt University (in Spanish). 13 November 2017. p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x LGBT+ PRIDE 2024 (PDF). Ipsos. 1 May 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "How people in 24 countries view same-sex marriage". 27 November 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe" (PDF). Pew. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Religious belief and national belonging in Central and Eastern Europe - Appendix A: Methodology". Pew Research Center. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Bevolking Aruba pro geregistreerd partnerschap zelfde geslacht". Antiliaans Dagblad (in Dutch). 26 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Discrimination in the European Union". TNS. European Commission. Retrieved 8 June 2024. The question was whether same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe.

- ^ a b c d e "Barómetro de las Américas: Actualidad – 2 de junio de 2015" (PDF). Vanderbilt University. 2 July 2015.

- ^ "63% está de acuerdo con la creación de una AFP Estatal que compita con las actuales AFPs privadas". Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b LGBT+ PRIDE 2021 GLOBAL SURVEY (PDF). Ipsos. 16 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ https://www.ciep.ucr.ac.cr/images/INFORMESUOP/EncuestaEnero/Informe-encuesta-ENERO-2018.pdf [dead link]

- ^ "Encuesta: Un 63,1% de los cubanos quiere matrimonio igualitario en la Isla". Diario de Cuba (in Spanish). 18 July 2019.

- ^ Guzman, Samuel (5 February 2018). "Encuesta de CDN sobre matrimonio homosexual en RD recibe más de 300 mil votos - CDN - El Canal de Noticias de los Dominicanos" [CDN survey on homosexual marriage in DR receives more than 300 thousand votes] (in Spanish).

- ^ America's Barometer Topical Brief #034, Disapproval of Same-Sex Marriage in Ecuador: A Clash of Generations?, 23 July 2019. Counting ratings 1–3 as 'disapprove', 8–10 as 'approve', and 4–7 as neither.

- ^ "Partido de Bukele se "consolida" en preferencias electorales en El Salvador". 21 January 2021.

- ^ "წინარწმენიდან თანასწორობამდე (From Prejudice to Equality), part 2" (PDF). WISG. 2022.

- ^ "Más del 70% de los hondureños rechaza el matrimonio homosexual". Diario La Prensa (in Spanish). 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Litlar breytingar á viðhorfi til giftinga samkynhneigðra" (PDF) (in Icelandic). Gallup. September 2006.